Journalism is facing both a trust crisis and a sustainability crisis. Membership answers to both.

It is a social contract between a news organization and its members in which members give their time, money, energy, expertise, and connections to support a cause that they believe in. In exchange, the news organization offers transparency and opportunities to meaningfully contribute to both the sustainability and impact of the organization.

It is an editorial orientation that sees readers and listeners as much more than a source of monetary support. Members actively contribute. In its deeper forms, it is a two-way knowledge exchange between journalists and members. It is an opportunity to identify your strongest supporters, and enlist them in your quest for impact and sustainability.

In many cases, membership is an agreement to keep access to journalism free for all. Many members don’t want a gate around the journalism they’re supporting. They are advocates for that journalism, and advocates have an interest in exposing as many people as possible to their cause.

Membership in news has three components.

A membership strategy defines where membership fits within the vision for your organization, including how you will sustain your journalism and the role audience members will play monetarily and otherwise.

Memberful routines are workflows that connect audience members to journalism and the people producing it. Routines are the basis for a strong membership strategy. Notice that audience members are specified here, which is likely a wider group than your members.

A membership program is the product your reader interacts with in becoming a member. It’s a container for managing the individuals who contribute to your organization. When people talk about membership, this is often what they refer to. It includes the page you land at when you click on, “become a member.”

Some organizations with membership do not yet have all three of these components, and there is a spectrum to the depth of each even when they do, but a participatory and inclusive newsroom at least partially sustained by members requires all three.

Membership is not the only audience revenue and engagement model available to news organizations. Understanding the different value propositions and resource demands of the different revenue and engagement models is key to understanding which is right for your community and your organization.

Defining Membership

When do membership models succeed?

Although membership in news is fairly new beyond public radio, it is not new to other movements for public good. That’s why Membership Puzzle Project studied churches, Burning Man camps, citizen science projects, and other member-driven movements for clues to survival. That research revealed five insights applicable to journalism.

There is deep value in listening, testing, and being fascinated with what members value. This is a mindset shift. Instead of just assuming what members want, successful membership organizations have developed ways of listening, fresh thinking about what their members actually want, and strong feedback loops to get it right. They’re empathetic and open to learning. They frequently adopt more agile approaches than they may have used in the past.

Inspiring membership-driven organizations connect individuals’ passions to a shared larger purpose. They sell more than a product or a cause. Successful membership organizations recognize and celebrate the individual while making them feel connected to something bigger than themselves. They get the ratio right between the individual and the group. This is neither a product pitch (“get 20% off exclusive content!”) nor a traditional “cause” (“save the whales!”). Getting that ratio right (which is hard because it often defies typical marketing approaches or advice) feels like a secret sauce for many of the successful movements MPP looked at. It influences how they think about the member mission, “social contract,” and pitch. This goes beyond offering plentiful member perks and relies on studying members’ intrinsic and extrinsic motivations.

Membership is one way to restore what feels broken. Many people told our team that they join as members because they feel something fundamental in the world and/or in themselves is broken. In membership they seek a way to feel part of a solution. Successful membership programs don’t shy away from connecting to the larger state of the world. They speak to the present zeitgeist in which something crucial is broken or out of balance — and then offer membership as credible grounds for optimism.

Offer flexible means of participation. The organizations MPP studied are attuned to people’s abilities, goals, limitations, and lifestyles. They offer multiple paths for participation, designed to maximize results from members’ time and effort. One of the reasons we say there is deep value in listening is precisely to discover how members do – and do not – want to participate. There is a whole range of ways for their supporters to participate in ways that are designed to maximize their time and effort.

Grow at human scale. Membership is an interaction among human beings, not a transaction. That means it can’t be fully automated, and that membership can’t scale beyond an organization’s ability to serve its members. In some cases MPP has seen organizations strategically limiting their growth to support members and ensure member value is not diluted. The research team thinks this has important ramifications for restoring the “human element” to news.

How is membership different from subscription?

In a subscription model, audience members pay for access to a product or service. It is a transactional relationship in which access to the content is what is monetized. This model typically requires a paywall of some kind. Subscription can scale much more quickly than membership because it doesn’t require engagement or a deeper relationship with readers. What it does require is exceptionally consistent, high-quality, highly differentiated journalism – and a good user experience.

For publications with strong institutional audiences in specific industries or that offer content that provides a strong professional benefit, subscription can work well. Publications like the New York Times, Wall Street Journal, The Financial Times, The Ken, and The Information have proven it. The success of The Athletic indicates that ardent fandom can also be a good foundation for an access-based model.

In 2017, Stratechery founder Ben Thompson explained why he chose subscription for his publication. It remains one of the clearest articulations to date of the value proposition for subscription. He writes: “First, it’s not a donation: it is asking a customer to pay money for a product. What, then, is the product? It is not, in fact, any one article. … Rather, a subscriber is paying for the regular delivery of well-defined value.”

The Ken, a business and technology journalism startup founded in Bangalore in August 2016, launched a subscription in October 2016. Head of Product Praveen Krishnan said that there were a few factors that took Ken down that path.

- They were committed to highly specialized, niche journalism, and they felt that it would be strong enough on its own that they didn’t need to offer additional benefits or participation for subscribers to find value in it.

- They were not trying to reach everyone, and they expected that their future readers would be people who could afford a subscription and would see their journalism as professionally useful.

- The deep knowledge among the team allowed them to easily provide the level of analysis that would set their work apart.

They’ve since launched a Southeast Asia version, also with a subscription. You can read more about their journey here.

How is membership different from donations?

In a donation model, audience members give their time or money in support of a common cause or common values. It is a charitable relationship. For publications with a coverage focus that can be strongly framed as a public good, a donation model can work well. If a coverage area is hard to build habit or community around – such as an organization devoted exclusively to investigative journalism that publishes irregularly or one that publishes primarily through partners – a donation model can also work well.

The line between donations and membership is fuzzier than the line between subscription and membership. Donations and membership are both cause-driven, and many of these newsrooms use the language of member and donor interchangeably.

In the U.S., donations are by definition tax-exempt, and are made to a charitable-purpose organization approved as such by the I.R.S. Some newsrooms fit this description. Meanwhile, the tax status of a membership contribution depends on the tax status of the sponsoring organization and can be either taxable or non-taxable. (MPP recognizes that this distinction does not necessarily apply outside the U.S. and encourages news organizations to seek legal counsel in their country on this question.)

What is different in a membership model as opposed to a donation model is the expectation of what a supporter gets in exchange. When trying to decide between the two, you should consider what level of editorial autonomy you need from your audience in order to fulfill your mission and what level of participation you’re willing to offer. Members expect to be able to engage with your organization (but not interfere – a critical distinction). Publications such as ProPublica and Mother Jones are strong examples of a donations model.

At Mother Jones, 71 percent of its 2019 revenue came from readers (they also have a print magazine subscription, which contributed 12 percent of its 2019 revenue of almost $17 million). The Shorenstein Center has more on Mother Jones’ editorial and revenue strategy.

Publisher Steve Katz sums the donations model that Mother Jones has had in place since its founding in 1976 as: “How does Mother Jones fit into the world, what kind of journalism are we doing that speaks to the challenges we face, and why does reader support matter to that?”

Mother Jones has a strong record of online reader engagement. Marketing director Brian Hiatt lists some of the key ways readers engage with the publication: reading their work, sharing their work, having conversations about their work, using their work for activism and local organization, and helping their reporting reach more people. All of those happen post-publication. This is a point where membership and donation models often diverge. In membership models, engagement often happens at all stages of the work, and readers have the opportunity to shape the coverage itself.

“At the end of the day, they’re readers, and at the end of the day, they help make it possible,” Hiatt said, although he noted that many donors self-identify as members because of the level of commitment they feel to Mother Jones.

How is membership different from crowdfunding?

In a crowdfunding model, audience members give a one-time contribution to support a specific project. Crowdfunding can work well for publications with a testable idea that can be tried with one-time fundraising and/or those who have the capacity for a sprint, but not a marathon. It’s a good way to test enthusiasm for an idea before reorganizing your entire newsroom to sustain it, and to learn more about your supporters.

Many organizations who eventually pursue a membership model have gotten their start with a crowdfunding campaign, treating the campaign as a test of whether people are willing to meaningfully support their organization. Crowdfunding can also be a way to build internal support for membership, as it did for 444 in Hungary.

How an internal communications plan helped 444 instill a member-focused culture

444's membership communications plan can be summarized as “Inform, involve, advocate.”

Some organizations execute a series of crowdfunding campaigns before transitioning to recurring support through membership, such as La Silla Vacia in Colombia, while some have considered their crowdfund contributors to be their first members and transitioned to a membership program immediately, such as Krautreporter in Germany and De Correspondent in The Netherlands. Some organizations, such as The Tyee in Canada and The News Minute in India, continue to run crowdfunding campaigns for specific initiatives even after launching their membership program.

How The Tyee plans a crowdfunding campaign in a week

Each campaign is built around a theory-of-change formula, and follows a time-proven template.

How The News Minute maintains crowdfunding and membership side-by-side

Crowdfunding activates readers who have no interest in the membership experience, but want to support specific projects.

How do we choose the engagement and revenue model for us?

An ill-considered membership try can lead to disillusionment and cynicism among people who become members but don’t ever receive opportunities for meaningful engagement in exchange. Membership is not subscription by another name, nor a brand campaign that can be toggled on and off.

If you are considering membership, it is critical that you think carefully about the level of editorial engagement you are willing and able to have with their audience members.

There are many trade-offs to consider when answering this question, including ones of staff time and financial investment. (Jump to “Staffing our membership program”; Jump to “Making the business case for membership”) Becoming member-driven is a culture change for most existing news organizations. That requires careful thought and determined leadership.

The next section, “How to know if we’re ready for membership,” will help you assess whether membership is the right path for your organization.

The three audience revenue and engagement models – membership, subscription, and donations – are not mutually exclusive. Blended models are increasingly common.

- The Guardian is a membership-based news organization. But it also offers several product-specific subscriptions and the opportunity to contribute one-time donations.

- The subscription-based Seattle Times has the donations-supported Seattle Times Investigative Fund. Many legacy metro news organizations in the U.S. aspire to membership as a hybrid between their overarching subscription model and a donations model.

- ProPublica operates as a donations-based model, but it also offers a level of audience engagement that is more typical of member-driven newsrooms. Donors might feel like members as a result.

- Malaysiakini makes its Malay content free, and offers subscriptions to its Chinese and English content. Subscribers are offered the opportunity to opt-in to a membership program, which includes the member-only online community, Kini Community.

The key to these blended models is clear communication with supporters so they can understand which mode of support most suits their motivation.

Paywalls regularly come up as an alternative model to membership. But paywalls are present in both subscription and membership models. It is one of many tools a news organization can use to incentivize audience members to pay. While the value proposition of membership in its ideal form includes an ethos of “I pay to keep news free for everyone,” many member-driven newsrooms have a paywall of some kind.

As researcher Eduardo Suárez wrote in February 2020, “The difference between membership and subscription models is more blurred than ever before. Some news organizations with a membership model run very hard paywalls while newspapers with subscriptions allow sampling opportunities through free trials, social and search. …The most successful news outlets are not attached to their models. They tweak them according to the behavior of their audience and experiment with bundles and revenue streams. The shape of your paywall must be just one of the elements of your value proposition.”

What do potential members want?

Early in its research, Membership Puzzle Project spoke to more than 200 people around the world who supported news organizations with their money, time, ideas, and expertise to understand what it was that motivated audience members to support the work. MPP found six common themes:

These themes do not replace the need for audience research. You still need to figure out how to deliver on these needs. Instead, view these themes as starting points for inquiries with your members about how to better serve them.

Involve me like you mean it: Sites that resonate are inclusive and participatory: they offer multiple ways for people outside the organization to take part and contribute what they know. There are relevant, personalized ways to be of service that aren’t the same old invitation to answer phone calls during public radio pledge drives.

Be real with me: Instead of presenting as a disembodied institution, supporters want staff and freelancers to show who they are, including what they’re currently working on, how people can contribute to it, and where they’re coming from. Supporters appreciate when site staff are transparent in showing how they make editorial decisions and how they spend supporters’ money and other sources of revenue. Even better is when they show what went into their stories (time, collaborations, travel, and more) and what actions audience members might take around stories they care about.

Be humble: People behind the organization are quick to correct themselves when they’re wrong. They recognize that they don’t have all the answers. They ask for help from others who might be able to offer it, including from their personal experience and professional expertise.

Stand out from the news of the day: Supporters use discretion in identifying news sites that produce high-quality coverage they can’t find anywhere else. They want those that offer smart takes on issues with depth, integrity, and a focus that is otherwise rare.

Make good use of my attention: The organization’s site, newsletters, podcasts, and/or apps feature a user experience design that is calm and considerate. This is different from the blaringly loud experiences that confront most visitors to news sites and television on a daily basis. Instead of attention grabbed, it’s attention granted.

Work always and only in the public interest: People increasingly want to back reporters and projects that they believe act in good faith and in their interest. As we’re seeing in journalism, government, social media, and other spaces, keeping our processes closed mystifies people and frustrates them. It can make it seem like we have something to hide, and that (understandably!) leads to distrust and dismissal.

What does membership look like when journalism is under threat?

Many of the recommendations you’ll see in this guide are based on an assumption that it is safe for you to be open about who your reporters and members are, what you’re working on, and where your money comes from. This is, of course, not universally true. MPP encourages news organizations operating in authoritarian and illiberal environments to see these recommendations as catalytic ideas, rather than instructions.

The Philippines’ Rappler, whose founder Maria Ressa was convicted of cyber libel in 2020, is the most prominent example at the time of publication. But from Hungary to Malaysia to Brazil, an assault on the press has complicated some of the core principles of membership, particularly transparency and participation.

At the time of publication, Malaysiakini editor-in-chief Steven Gan faced charges of contempt of court for several comments left by readers on a story. That has stifled the vibrancy of Kini Community, their online community, driven by concern that Malaysiakini will be forced to disclose who its subscribers and members are and that the government might retaliate against them in some way. Malaysiakini has a blended model that offers subscribers the opportunity to participate in memberful activities, including Kini Community, but does not require it, partially because being a “member” of Malaysiakini is more fraught than being a subscriber.

Why Malaysiakini blended membership and subscription

Given the government’s attacks, Malaysiakini understood people might be nervous about being “members” – but knew they wanted to engage.

Atlas.zo in Hungary has been navigating this challenge for years. At the Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN) Conference in 2019, editor Támas Bodoky recommended that news organizations make it possible for people to contribute money anonymously, including via money order, and to lean into government aggression as a reason to support a news organization.

In cases where a high level of transparency could bring emotional or physical harm to your staff, you might instead share what you can about why you are safeguarding information and how it ties into your mission.

How deeply should we involve our members?

The degree in which your newsroom engages its members lies on a spectrum. On one end there’s “thick” membership and on the other side there’s “thin” membership.

In the process of compiling the Membership in News Database, Membership Puzzle Project began distinguishing between “thick” and “thin” models of membership. At the “thin” end of the continuum, members mostly resemble donors. They are expected to lend financial support and read and share the journalism. This might be an organization with a membership program, but not memberful routines. Many public radio stations traditionally fit this description, although most of their membership programs are becoming much more participatory today.

As membership programs reach a certain size, they might move closer to the thin end of the spectrum. Due to the sheer scale of The Guardian’s membership program – more than 800,000 members as of April 2020 – the organization has had to limit how often it offers opportunities for deeper engagement. This is why membership has to scale differently than other revenue and engagement models.

At the “thick” end of the spectrum, members still give money and read your journalism, but they also show up at events, offer advice and feedback, respond to call-outs, share their knowledge, and interact with journalists. This relationship is denser and more intimate. It engenders a constant feedback loop between the news organization and its members, and the news organizations at this end of the spectrum typically offer different participation opportunities that are appealing to different types of people. There are many subscription-based organizations who have cultivated this “thick” relationship with their subscribers. They have memberful routines, but not a formal membership program.

One of the “thickest” forms of membership is offering actual ownership to your members, as news cooperatives do. At cooperatives such as the Bristol Cable in the U.K. and The Devil Strip in Ohio, U.S., members are also shareholders. Through channels such as annual general meetings, they play a role in strategic decision-making. At the Bristol Cable, member-owners elect the board of directors (and can run for a seat) and have also helped the staff do things such as craft an ethical advertising policy.

Both the “thick” and “thin” styles have their advantages. The thin model is less expensive in staff time and infrastructure because coordination costs are close to zero and transactions can be automated. It’s also more plausible for time-starved members.

The thicker forms of membership create deeper bonds between the site and its supporters, and they are more likely to pay dividends for the journalism itself. They also address head-on the opacity and distance from the community that has led to deep distrust between news organizations and the communities they serve. But thicker member engagement models consume more time and require shared effort across news, development, and marketing staff.

And, of course, not everyone who supports your organization wants to participate. Red/Acción in Argentina emphasized the participation opportunities that membership offered so strongly that some readers admitted that they considered cancelling their membership because they felt guilty for not utilizing those opportunities, which were framed as so central to the experience.

For many members it will be enough to see that you offer those opportunities and that others avail themselves of them. De Correspondent’s member participation adheres to the 90/10/1 rule: 90 percent of members will just consume the product, 10 percent will interact with you, and 1 percent of that 10 percent will become core contributors.

How profitable will membership be for us?

This is another area where offering the answer as a spectrum is helpful. Membership as a source of revenue exists on a spectrum from “lifeline” (which MPP uses to describe organizations where membership makes up more than half of revenue) to “discipline” (where it makes up only a fraction of revenue, but helps cement an audience-centric newsroom culture). Membership is almost always an effort to diversify revenue, and there are very few organizations that are wholly or almost wholly supported by membership revenue. (Jump to “Making the business case for membership”)

Mature small-dollar-supported digital newsrooms in the U.S. such as the Texas Tribune, VTDigger, and Mother Jones bring in between a fifth and a third of their revenue from small givers, many of whom are members. Some younger member-driven digital newsrooms have also been able to reach this level of 20 percent to 33 percent revenue support from membership. Roughly 25 percent of the Daily Maverick‘s revenue comes it’s two-year-old membership program. With enough investment in a strong member experience, membership can become a newsroom’s dominant source of revenue, as it has at De Correspondent, El Diario, and WTF Just Happened Today.

Many organizations pursue membership both for the revenue and because the practice of serving members, particularly when distributed across the entire newsroom, offers a certain discipline and infrastructure that can help cement audience-centric practice. Membership also offers a strong demonstration of community traction for potential funders.

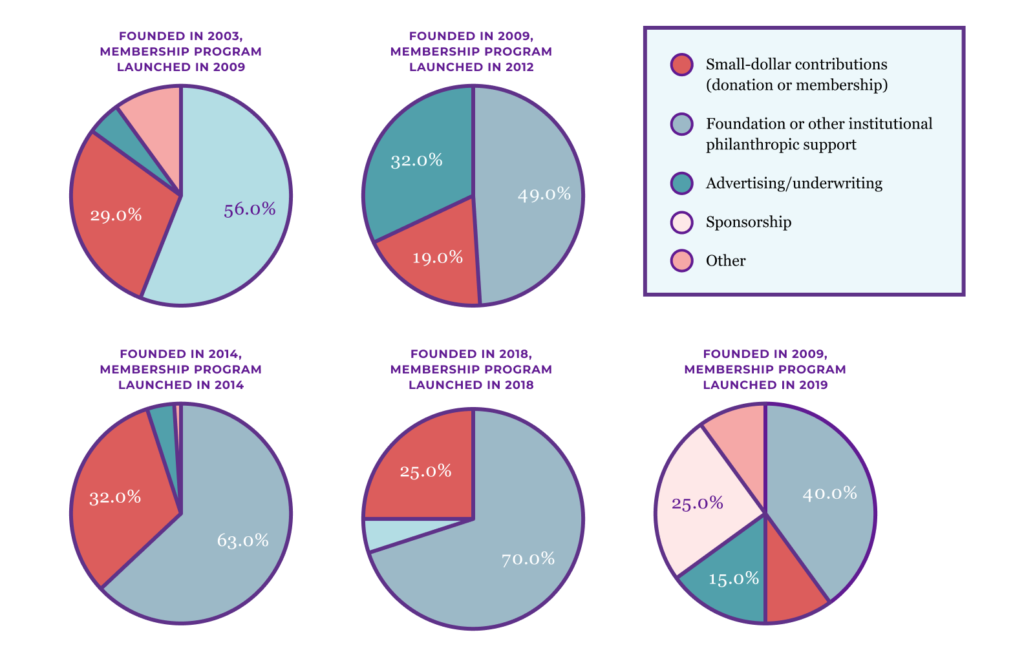

In MPP’s dataset of 40 member-driven newsrooms around the world, six newsrooms saw membership contribute between 20 percent and 33 percent of their total revenue. Below, the research has chosen and anonymized a few responses, all from primarily digital newsrooms, that exemplify different revenue mixes.

Three of these examples are from North America and two of these examples are from Europe. (While MPP also received responses from Latin America, Africa, and Asia, MPP is not sharing those revenue mixes out of respect for the newsrooms’ anonymity. Some of the specifics of their funding sources made them easily identifiable.)

As the number of newsrooms pursuing membership has expanded, another question about its sustainability has emerged: is membership a viable source of revenue for a newsroom serving a low-wealth or otherwise traditionally excluded community?

It’s too early to say definitively what role membership will play for those newsrooms, said Courtney Lewis, chief of growth programs at the Institute for Nonprofit News (INN), when the research team interviewed her in 2022. Lewis has spent the past couple years observing U.S.-based nonprofit newsrooms’ experimentation with membership, especially during the INN-run annual NewsMatch campaign.

Membership has the potential to be a valuable source of revenue for newsrooms serving low-wealth communities, but Lewis and MPP suggest that it will take a different form than most of the newsrooms that MPP has studied because those most served by their work may have limited wealth or discretionary income to give. Their value as a news provider may be more accurately expressed through their impact, not the size of their membership base or revenue.

Citing data from INN’s Index Report, Lewis said that although individual giving is one of the fastest growing sources of revenue for nonprofit news organizations, formal membership programs make up only 7 percent of individual donor revenue.

But she cautions against seeing small shares of membership revenue as proof that membership isn’t working for these organizations. “It’s not that membership is a faulty tool. It has a different purpose,” she said.

Based on Lewis’s overview of the challenges and opportunities, MPP has two recommendations for newsrooms serving low-wealth communities who want to pursue a membership strategy.

Think of membership as a discipline, not a lifeline. When the research team talks about membership as a discipline, as it did earlier in this section, it is talking about memberful routines: workflows that connect audience members to the journalists and journalism. When done intentionally, memberful routines can reveal an audience’s true information needs. If a newsroom pays attention to those needs and designs for them, it might be able to secure philanthropic support for the product it creates in response.

Think of yourself as having two target audiences: the people who need your journalism, and the people who want to support that journalism. You should be pitching membership to the second audience. Many of the members that MPP interviewed said that they became members of an organization because it felt like a way to restore something in the world that felt broken. If you can prove that your journalism is genuinely reaching and helping an underserved audience, you can make the case that supporting your journalism is a way to support that community. Membership can give supporters a way to become part of the solution. Whether they need the journalism that you produce becomes secondary in this case.

MPP has also received questions over the years about whether membership can be profitable for newsrooms in countries with challenging economic climates. The research team has seen membership become a viable source of revenue for newsrooms in such environments, including the Daily Maverick in South Africa and 444 in Hungary. Furthermore, MPP encourages newsrooms operating in countries with large diaspora communities to consider whether the audience in the diaspora presents a particular membership opportunity. (Jump to “Should I design a membership opportunity for audience members in the diaspora?”)

How do we balance membership with our commitment to equity?

Membership is a subsidy system in which those who can afford to support journalism do so, at least partially to ensure that it continues to be available for everyone. But there is a growing tension between member-driven newsrooms’ public service mission and having a membership program, which inherently trends toward exclusivity.

Some organizations are OK with having insiders. But an increasing number are grappling with how to reconcile their commitment to equity and inclusion with a membership base defined by financial support that is wealthier and less diverse than that of the community the news organization exists to serve. This tension is particularly pronounced in societies where those who can afford to pay for news are in the minority.

Rather than try to eliminate this tension, Membership Puzzle Project recommends that news organizations identify it and own it. Here are three examples.

Scalawag, a digital magazine about the American South, “illuminates dissent, unsettles dominant narratives, pursues justice and liberation, and stands in solidarity with marginalized people and communities in the South.” Their membership base is whiter and wealthier than the community they exist to serve. For them, membership is a form of wealth redistribution and media reparations.

City Bureau, a civic journalism lab in Chicago, has a membership program for people who provide recurring financial support. They also have their Documenters, Chicagoans they train and pay to attend and document local government meetings. Documenters aren’t members in the traditional sense – instead of financially supporting City Bureau, City Bureau pays them. But in City Bureau’s mind, both the Documenters and financial supporters are members. Maldita in Spain has a similar arrangement. They have their ambassadors, who are their financial supporters, and they have their “superpower contributors,” which is made up of readers who have volunteered to use their expertise to help Maldita fact check misinformation.

For Frontier Myanmar, an English and Burmese startup based in Yangon, membership is a bundle of elite products that allows them to keep the core journalism work freely accessible in both Burmese and English. The Frontier team knew going into their membership launch that the majority of the readers who could afford to pay would not be local. Eighty percent of their members are expatriates in Myanmar or people outside the country.

Can membership exist alongside cooperative ownership?

The short answer is yes. But first, let’s talk about what a cooperative is.

A cooperative is an organization that is democratically owned and operated by individuals who each have one vote in the decision-making process. Co-ops are found across industries, including in journalism, and there are a number of different models of co-ops. For example, The Associated Press is a shared services co-op and the sports news site Defector is a worker-owned co-op. The most common cooperative models in journalism are worker-owned, audience-owned, and multi-stakeholder cooperatives.

A worker-owned cooperative is a business that is owned and managed by its employees. One example of a worker-owned news cooperative with a membership program is Tiempo Argentino in Argentina.

Community-owned cooperatives, often known outside the journalism industry as consumer cooperatives, are businesses owned by the people that patronize them. In the case of journalism, that means its audience members. Examples of community-owned news cooperatives with membership include the Bristol Cable in the U.K. and the Devil Strip in Akron, Ohio.

Multi-stakeholder cooperatives, or hybrid co-ops, are owned by more than one group of members. The Ferret and the New Internationalist in the U.K. are multi-stakeholder news cooperatives owned by both their workers and community members.

In a worker-owned cooperative with a membership program, members are a source of financial support and likely also engage with the newsroom more deeply than other audience members. However, members are not shareholders, nor are they legally entitled to a decision-making role.

Javier Borelli, the former president of worker-owned cooperative Tiempo Argentino, told MPP that although members are not owners, and therefore not entitled to a role in major organizational decisions, they still trusted Tiempo more than privately owned newsrooms in the market because the staff members were also the owners. When Tiempo asked members why they supported the newsroom, members frequently cited the transparency about decisions and the horizontal decision-making structure that are critical components of worker ownership.

In community-owned and multi-stakeholder cooperatives, the members are also the owners and anyone who joins gets a say in how the organization is run.

The Bristol Cable in the U.K. is a community-owned cooperative. Anyone who contributes at least £1 per month becomes a member/owner. Each year, the Cable has an Annual General Meeting where it asks its member-owners to elect a board of directors, approve the outlet’s budget, and vote on topics such as editorial campaigns the Cable should pursue and the types of advertising it should accept.

How The Bristol Cable made decision-making accessible to all members

The Bristol Cable enabled online voting to make its Annual General Meeting accessible to a broader swathe of members.

The community-owned/audience-owned co-op model is the “thickest” form of membership, and requires extensive engagement with your members because they are legal shareholders and therefore must be consulted when making decisions affecting the organization (as opposed to other forms of membership, in which engagement is typically something the newsroom offers as part of an informal social contract).

Not every newsroom is set up to support that. Co-operatives UK, a British organization supporting co-ops, outlines three essential questions anyone thinking about creating a co-op should be able to answer affirmatively:

- “Do you want members to own and control the organization?” As a co-op, members have an equal say in how the outlet is run and how to manage the finances. You need to be okay with members having their say on key editorial and business decisions. You also need to create frameworks — such as the Bristol Cable’s AGM — that allow for meaningful contributions.

- “Can your business work with co-operative values and principles?” Those values and core principles include transparency, openness, community-centered social responsibility.

- “Have you got a viable business idea?” Even as a co-op you still need diversified revenue streams to support the business. The resources in Making the Business Case for Membership can help you assess your revenue opportunities.

Sound like something that might be a good step for your newsroom? The following are places where you can dig deeper into cooperative ownership.

- The News Co-op Study Group wiki: For a deeper explanation on how co-operatives function and what it takes for them to succeed, we recommend visiting this collection of resources curated by Olivia Henry.

- The University of Wisconsin Center for Cooperatives: The laws and regulations governing cooperatives vary from country-to-country and state-to-state. Head here for a curated list of resources on co-op governance, finance, and legal requirements tailored to U.S.-based cooperatives.

- International Co-Operative Alliance: This organization publishes global research and country-by-country legal frameworks for cooperatives.