Audience research is a listening process. It uncovers what your audience members and potential audience members want or need. It can reveal both how people engage with your work and what motivates them to do so.

Without audience research, questions about who the audience is and what it “wants” tend to be answered based on hierarchy or power within your organization, or based on assumptions about who your audience is. That isn’t good enough in an organization that is dependent on audience revenue and participation to survive and fulfill its mission.

Audience research helps you determine whether you’re building something that is desirable. Useful, desirable products build habit and loyalty – and it’s habit and loyalty that will bring your audience members closer to your newsroom and eventually turn some of them into members. Audience research will be your tool to collect feedback, assess member satisfaction, and adapt to changing needs along the way. It can also help prevent you from investing in things that members don’t want. To put it simply, audience research sets you up to stop making guesses about your audience members’ needs, and to start developing informed hypotheses that you can test.

Here’s another way to think about it: volunteering to be a part of audience research is one of the simplest forms of participation you can offer to members. It’s valuable on its own, but it might also be the first step on a path to greater participation. If you’re a member-driven newsroom, you always need people to help you out by taking a survey or sitting for an interview. If someone asks you, “What can I do other than give money?” the easiest answer is usually “Tell us what you think about this” or “Fill out this survey.”

This section will walk you through how to use audience research to gather the information you need to develop your membership strategy, including a breakdown of what different types of audience research a member-driven newsroom might undertake and the questions audience research can help you answer.

The goal of this section is to help you:

1. Identify what type of audience research will get you the information you need

2. Conduct that audience research

3. Synthesize your responses into insights

4. Act on those insights

MPP sees “audience research” as synonymous with “user research” and opts to say “audience” instead of “user” because it is important to speak about your fans, readers and members in a term that recognizes their humanity beyond their use of your product.

Conducting Audience Research

What are audience research best practices?

Getting the question and method right is only half the game of doing audience research well. The other half is ensuring that the process and principles you have in place for conducting and using audience research will support real insight, and build a strong relationship with your audience. Before you begin, consider the following:

Audience research should always be undertaken in connection with a specific organizational goal. The first step in audience research is to identify what you need to learn from it. Once you have a clear goal in mind – whether that’s how often you should send a newsletter or what benefits your members want – write a short research brief to help you narrow your sights. You can see the brief the Membership Puzzle Project wrote to guide a research session with De Correspondent’s members in 2017.

Without a clear goal, it will be hard to gain actionable insights. You’ll want to be sure that you can imagine taking an action or making a change to your workflow, products or coverage areas as a result of data and findings.

How De Correspondent refreshed its member insights

Four years after launching their membership program, De Correspondent sat down with members to find out what they thought.

Make inclusion and accessibility central considerations. Research recruiting bias occurs when “certain individuals or groups are excluded from the focus group for reasons not specified in the research plan.” For example, recruitment solely through online news outlets limits access to those who meet their news needs offline, such as the elderly, or those who cannot afford an internet connection. Another recruitment bias could be English-only communications that exclude non-English speaking groups,” the Local News Lab warns. Using random selection is an important step for avoiding recruitment bias in your audience research. Beyond DEI considerations, newsrooms will receive better insights when they go beyond a subset of people with the bandwidth and resources to easily participate.

Remember that audience research is about challenging assumptions and stereotypes about your members or target members. It is imperative that you approach an audience research process with clear-eyes on your own assumptions and stereotypes about your audiences. Don’t wall yourself off from adapting how you view your audience and their needs after the results come in. Or in other words, try not to let any “lore” about your audience affect the interpretations of the data. It could be a good idea to write down any assumptions you might have about your audience beforehand, so you can have a record to refer back to. If you don’t allow your audience research to influence your thinking, you could sabotage your work before you even launch.

Keep cultural context in mind when choosing what questions to ask. MPP will offer suggestions for what questions to ask at several points throughout this guide, but you know your audience best. Asking questions that might offend people or make them feel exposed will erode trust. Topics such as income level and gender should be addressed carefully and inclusively, informed by your cultural context.

Make it clear with audience research subjects how you intend to store and use the data. Before you get started, decide with your team how you’ll do things such as anonymize the data and whether you’ll share any of the findings publicly. Disclose that to participants as clearly as possible, and be sure to store any data you collect appropriately. Using data inappropriately will undermine trust with participants. For more on that, see this article by Mary-Katharine Phillips on knowing your readers in a world with privacy regulations.

Make sure to allocate enough time for synthesis. You should allocate at least as much time and bandwidth to analyzing your data as you did to designing your method and collecting responses. The quality of your insights — and the effectiveness and actionability of your conclusions — will be directly related to how much time you spend analyzing your data – which includes talking with each other about what you heard.

Be grateful for your audiences’ participation. Say thank you early and often to anyone who participates in your audience research. Tag them in your CRMs or systems as someone who has participated so you can acknowledge their efforts if you ever ask them again. Some researchers give gift cards or other monetary rewards for participants. The research team recommends sharing back anonymized and/or aggregated results with participants. It reinforces that your membership program is a community that learns from and supports each other.

Make audience research a continuous process. Audience research doesn’t end when you’ve launched your membership program or identified a new way for audience members to participate. You should also find ways to continually gain new insights into what your members value. Organizations that are in regular communication with current and potential members are more easily able to identify new membership products that are useful on both sides.

How VTDigger gets and uses a steady flow of audience feedback

Their suite of surveys and commitment to always following up with respondents gives the staff a highly useful picture of their audience.

What are the common methods of conducting audience research?

Once you’ve identified what question you’re trying to answer with audience research by defining your goal, you have a number of options for the “how.”

Build on Existing Research

The first place to start when trying to answer a question with audience research is to look for existing materials and research on your subject. The annual Digital News Report from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism is often a useful starting point. For competitive and market research, the research team refers you to desk research or comScore, or your region’s equivalent.

The following entities frequently publish or highlight research that might be useful (listed in alphabetical order):

- American Press Institute (U.S.)

- City University of New York’s Center for Community Media (Primarily U.S.)

- European Journalism Centre (Europe)

- Knight Center for Journalism in the Americas (North and South America)

- Knight Foundation (U.S.)

- Pew Center (U.S.)

- Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (Global)

- Sembra Media (Latin America)

- Splice Newsroom (Asia)

- Tow Center for Journalism (U.S.)

Look at your metrics

Next, you’ll want to look at your metrics. In general, questions about how people behave – such as how often they are reading your newsletter or what time of day they open it – are best answered by looking at metrics. Depending on what you’re trying to understand about your audience members, you might find everything you need to know in your data.

But if you have questions such as how audience members feel or think about something, that will require other research methods. Patterns in your metrics might also end up raising questions about your audience members’ behavior that require a survey or interview to answer. Not sure what metrics to track yet? Jump to “Developing membership metrics” for more on how to design a metrics strategy that gives you actionable audience insights.

Use surveys

Surveys are the most common medium for conducting audience research, and can be particularly useful when trying to collect specific feedback or quantitative information on your audience. Surveys are a good way to collect a lot of responses quickly, so if a large sample is more important than nuance for the question you want to answer, then a survey is a good choice.

Surveys are not good for when you need information on your audience underlying motivations, habits, or needs. For this type of data collection, we recommend focus groups or interviews — see the section below for more on these methods.

Conduct interviews

Interviews are time and labor-intensive, but they can yield incredible insight when done well. Interviews are a good fit for understanding motivation, for drilling down on attitudes or feedback, and for eliciting new ideas. Interviews are also useful when you need to be very intentional about who you receive feedback from. Interviews are not great for cataloging behavior. People are notoriously bad at objectively reporting on their own behavior, and your metrics will give you a more accurate picture of audience behavior.

Interviews can be your primary means of audience research, or can be done in connection with a survey. You can offer interviews as an additional opt-in at the end of an audience research survey (the last question of a survey can be, “would you be willing to speak with a member of our team for 30 minutes on the phone?”). You could also start with a series of interviews to figure what to focus on in a survey you send out to your entire audience.

| Consider interviews | Consider surveys |

|---|---|

| When you need to be very intentional about who you receive feedback from | When you need responses about specific or niche uses |

| When you are looking for detail on why individuals think, consume information, and purchase in the ways they do | When you need information from a broad, geographically distributed group of people |

| You need new ideas | When you need quick feedback on work-in-progress |

Hold focus groups

Focus groups are a good way to get a lot of qualitative feedback quickly, and can be a good compromise when you need more nuance than a survey can offer but don’t have the resources to do many 1:1 interviews. They also provide a rare opportunity to see how people can push each other’s thinking.

You can run a focus group by selecting a handful of people (we recommend between five and ten people who are representative of the audience members who matter most for your topic or question). Too few and the conversation could lag, requiring intervention from your team, too many and you won’t hear enough from any one individual to gain actionable insights.

What are best practices for surveys?

Below is a suggested workflow for conducting a survey of your audience members, informed by the research team’s own experience and Krautreporter in Germany’s survey best practices. Membership Puzzle Project has also created a library of more than 70 survey questions. Surveys can be used at every stage of a newsroom’s work.

Choose your survey tool. MPP recommends picking an online survey platform that can be easily used by your team, fits your budget, and is mobile-friendly. MPP has had success with tools like Google Forms, Typeform, and Survey Monkey. Krautreporter uses Typeform (and here is the Typeform template they use).

Design your survey format, flow, and questions. Next, you’ll craft the substance and order of your survey questions. MPP recommends keeping your surveys short (the longer the survey, the fewer completed questionnaires you can expect to get back) and that you consider including questions that can be answered with radio buttons and Likert scales to set you up for an easier analysis.

Open-ended questions take longer for participants to answer and are often tricker to analyze, but can give you more detail and nuance. It’s worthwhile to use an open-ended question when you aren’t yet aware of the possible responses or scenarios (e.g., you don’t know where to start with the multiple choice responses to provide).

Organizations with a highly engaged audience might have success with long surveys (Black Ballad in the UK has successfully conducted 100-question surveys on topics such as Black motherhood, for example), but they should be used sparingly and only after your organization has tested your audience members’ appetite for this with shorter surveys.

Here are a few other things MPP recommends while designing your survey:

- Introduce yourself at the start of the survey. Tell the respondent who you are, the organization you represent, and the purpose and topic of the survey.

- State how long you think it will take your audience to complete the survey. You may also want to give your respondents a deadline to complete the survey.

- At the beginning, include a brief note about what work the survey responses may inform and how their confidentiality will be protected. (See examples in this online survey consent form from the Institutional Review Board (IRB), this opioid abuse coverage survey introduction from the New York Times, and this more detailed disclaimer template from SurveyMonkey.)

- Thank the respondent for taking the time to complete the survey, and tell them how important their feedback is for your membership program.

- Ask for the respondent’s name and email address, as well as consent to contact them with follow-up questions and updates on how the research informed your work. (You can make this optional if you are worried it will suppress your response rate to not allow anonymous responses.)

- Consider including an opt-in or opt-out to your newsletter or however you communicate regularly with audience members.

Test your survey. Ask a friend or colleague to take the first spin and check for any bugs or confusing language. If you have used members as product testers in the past, this is a good opportunity for that. Testing will also tell you how long the survey will take to complete, something you should include in your request to complete it.

Distribute your survey. Consider where you can best reach your members (whether it be via your newsletter, your website, social media, or all of the above). The research team has seen the highest response rate when the survey is sent via email newsletter (with perhaps a reminder or two targeted to the portion of your list that hasn’t opened or completed your survey). When posting a survey to social media, Krautreporter recommends including the main question in the post and using a minimum amount of branding, so the focus is on the question. If you need to get beyond your audience, consider partnering with another institution to get the word out, as the Compass Experiment did with the local library in Youngstown, Ohio.

To analyze survey results, jump to “How do we generate insights from audience research?” For more best practices on designing and distributing surveys, see WBUR’s Media Audience Research.

What are the best practices for interviews and focus groups?

Best practices for more qualitative data collection methods, like interviews and focus groups, include similar design tips to those mentioned in the survey best practices above. Below, the research team shares a few pieces of advice specific to these more engaging and time-intensive audience research strategies.

Be intentional about who you interview. You should talk to no fewer than seven people to be able to identify trends and outliers. It’s also vitally important to ensure that an appropriate balance of individuals is represented. Consider how to avoid recruitment bias by making the language and technology of your call to action accessible to the audiences you are trying to reach, and if you’re holding the interviews or focus groups in person, consider the location preferences (and public transport options) of your participants. See here for more from the Local News Lab’s advice about the importance of avoiding recruitment bias.

When MPP worked with De Correspondent in summer 2017 to hold focus groups to learn what its members valued about their membership, it implemented a two-step recruitment process. In order to ensure a variety of occupations, ages, educational backgrounds, membership tenure, and behaviors on and off platform in the focus groups, MPP first sent out a screening survey via Google Forms to everyone who indicated interest in participating.

Here’s an exception to the above: there can also be a benefit to seeking out your “extreme users” for your interviews or focus groups, or a particular subset of your audiences that are the mega-fans and frequent readers. This process is most beneficial when you already have a good sense of who your “extreme users” are, but would like to dig deeper on their preferences, habits, motivations, or needs. This recruitment process will be a bit more targeted than the one described above. See this guidance from the Stanford d.school for more.

Meet in a neutral space. MPP recommended offering to meet participants in their homes or reserving a neutral space where you can record the session with participants’ consent (no coffee shops or public spaces, since MPP believes having other people around will inhibit what participants share with you).

MPP is writing this in the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, when in-person meetings are strongly discouraged. Those who can’t delay their audience research are doing remote focus groups via Zoom. The research team recommends that newsrooms use online focus groups sparingly, and instead leverage online one-on-one interviews as much as they can. For advice on hosting focus groups during a pandemic, the research team directs you to this guide from UXAlliance.

Make your participants comfortable. Introduce yourself to your participant(s) and your project, even if they’ve received the information in writing already, and ask if they have any questions before getting underway. If you’re conducting a focus group, we recommend asking your participants to take turns introducing themselves before you get started (perhaps with their name, a bit about themselves, and how they came to be here today) to break the ice with the group. Encourage conversation at this stage and draw connections based on your participants responses (e.g., “Interesting, both of you joined this session because you loved our last virtual event!”)

In terms of good questions for an interview or focus group format, see MPP’s questions in this discussion guide for a list of introduction questions, background information, media habits, membership interactions and ideas, and more.

For focus groups specifically, here are a few of MPP’s tips:

- Have both a notetaker and moderator on hand and be sure to request consent to record if you want to do so.

- Prep the focus group moderator with a set of question prompts and follow-ups to help guide the discussion.

- Ensure you elicit contributions from each participant of the focus group.

- Encourage focus group members to build on each other’s insights.

- Thank your focus group participants, and follow up with the insights you gleaned and what you are going to do with them.

See MPP’s Hack our user research materials for more material on exercises you can conduct with your participants.

Next we’ll go through three key audience research inquiries for member-driven newsrooms. If you’re not sure what you need at your stage of membership, try the Audience Research Compass, which asks a few simple questions in order to direct you to the right inquiry.

How can audience research tell us if membership is viable?

A membership viability assessment is an inquiry into the depth of your relationship with audience members, whether and how much they would be willing to support you financially, and what they value about your organization.

This is most useful pre-launch, but you could also conduct the values portion of this assessment after launch to iterate on your membership program and refine your pitch. It should be relatively brief. If this research inquiry reveals that membership is viable, jump to “Designing our membership program” for follow-up research.

Questions you could ask to assess whether they would be willing to support you financially include:

- How long have you been a reader/listener?

- How likely are you to recommend us to a friend? (With answer options ranging from “highly unlikely” to “very likely)

- Do you financially support any other news organizations? If so, which ones?

- What causes and organizations do you financially support?

- How much do you give monthly or annually to causes and organizations you elect to support?

One tool you can use during a membership viability assessment is a Net Promoter Score (NPS). News Revenue Hub uses this with its clients.

Essentially, a NPS is the answer to this question: “How likely is it that you would recommend our company/product/service to a friend or colleague?” The scoring is based on a 0 to 10 scale, with 10 being most likely to recommend. The score helps you gauge the level of enthusiasm your loyal audience members have for you. If you are above a 7, you have a strong promoter contingency – a good sign for membership. MPP offers more advice on using NPS as a feedback tool later.

You could use an NPS survey in two ways. You could include it as a question in your broader membership viability survey (potentially as a replacement to the question “How likely are you to recommend us to a friend?” or something similar) or you could send it out on its own, in place of the broader survey. The latter gives you fewer actionable insights, but can quickly confirm whether you have an enthusiastic enough audience to launch a membership program.

Many organizations ask directly whether respondents would be willing to financially support them with questions such as “Would you be willing to financially support us on a monthly, recurring basis?” and “How much would you be willing to pay on a monthly basis?” You can do this, but it’s not a particularly strong indicator of whether they actually will support you when you launch your membership program. People don’t always answer hypotheticals accurately. MPP recommends assessing readers’ likelihood of becoming a member by assessing how much they value your work, which is why we include the question “How likely are you to recommend us to a friend?”

Asking audience members what they value about you before launching a membership program will give you useful data about how they emotionally connect to your organization – the basis of a membership value proposition (Jump to “Discovering our value proposition“) and strong membership appeal – as well as what types of benefits will resonate with your future members. But you can also ask this at any point in the life cycle of your membership program.

The following are six questions you could ask:

- What do you turn to [newsroom] for?

- What work by [newsroom] do you value most?

- What work by [newsroom] do you read most often? (Answers could be about format, such as daily news stories, newsletters, or podcasts, or particular beats or coverage topics.)

- What do you value most about [newsroom]? (You could adapt MPP’s member values worksheet for this for suggested answers)

- What other causes and organizations do you support?

- What motivated you to support them?

MPP also encourages you to come up with your own mix of questions that speak to what you need to know. You can peruse the library of survey questions for suggestions.

If you already have a loyal audience and a way to reach them directly, such as by email, you can ask these questions with a simple survey. They could easily be combined into a larger survey of your audience members, like Radio Ambulante did in 2019, four months before launching its membership program. In their annual audience survey, Radio Ambulante included two questions that gave them encouragement that membership was viable:

- Would you support the production of new podcasts with a monthly subscription? (59.1 percent of their more than 6,000 respondents said yes)

- If you do want to support us, how much would you be able to pay monthly? (65.2 percent said $5 a month, and another 18.6 percent said $10 a month)

The survey also included many demographic questions, which helped the team understand how willingness to pay varied with factors such as country, profession, and number of years listening to the podcast. Radio Ambulante used the term “subscription” in the survey because they were not sure that the term membership would be understood without proper context, which they couldn’t provide in a survey.

The Daily Maverick sent a membership viability survey to its previous one-time donors. You can see their survey, the responses, and how they used that to design their program in MPP’s case study.

How Daily Maverick tested its membership assumptions pre-launch

Daily Maverick took advantage of a delay with its membership program launch to answer some questions it had about its potential members.

MPP’s library of survey questions includes examples of demographic and behavioral questions that you could include.

If you are not yet publishing and don’t yet have a loyal audience, MPP instead recommends assessing general willingness to pay for news (with questions like, “Would you be willing to pay for a local news service that reports on X and Y?”), and what they want in a news organization.

You might have to partner with another organization (perhaps a local library chapter, or a civic or nonprofit organization in the community you are serving) to attract a large enough group to participate in focus groups or interviews on these subjects. That’s what the Compass Experiment did.

How Compass Experiment did audience research before it had an audience

Finding partners is key to conducting useful pre-launch audience research.

If you’ve confirmed that membership is viable for your newsroom, you might now jump to “Designing your membership program.” MPP offers a step-by-step process for leveraging these insights to build a program that resonates.

For more on propensity to pay and value assessments, MPP recommends:

- From WBUR, the results of audience research with their members identified four key drivers for repeat consumers of their products, including personal life changes, geographic pattern changes, national and world events, and quality journalism and captivating programs.

- From American Press Institute, research that revealed people pay for news that reinforces their social identities.

- From American Press Institute, research that identifies 3 types of news subscribers and explains how to convert them.

How can audience research help us understand member motivations?

Your audience is not a monolith, especially when it comes to their motivations for participating in and supporting your work. If you want to have a true two-way relationship with your members – in other words, if you want to have memberful routines and/or a thick membership program – you’ll need to understand the different motivations.

Understanding what motivates your audience members to participate allows you to segment your audience members so that you can identify and offer desirable participation pathways. Participation opportunities and membership benefits that aren’t grounded in audience member motivations are unlikely to be utilized – a missed opportunity. The MPP team calls this type of questioning a “motivations assessment.”

For example, from analysis of audience research with hundreds of supporters of news organizations, the Membership Puzzle Project found six key motivations for participation.

Curiosity and learning: Audience members who are motivated by their curiosity will participate in order to learn something new, whether that’s new knowledge or a new skill.

Show a superpower: Audience members who are motivated by the opportunity to contribute their expertise have a useful skill that they see an opportunity to employ to make your work better.

Voice: Audience members who are motivated by the opportunity to have a say have an opinion, experience, or question that they feel needs to be part of the conversation.

Transparency: Audience members who are motivated by the opportunity to get the inside scoop want to understand how and why journalism is produced.

Passion: Audience members who are motivated by the chance to show some love for your mission are proud of their affinity with your organization and want people to know about it.

Community: Audience members who are motivated by the chance to be a part of something bigger than themselves want to see and feel the community around your work.

This list captures the six most common motivations MPP heard, not the full range of responses, and your audience members’ motivations might vary from these. Here are some questions from MPP’s library of survey questions that you can ask either in a survey format or in interviews or a focus group to assess motivations and capacity to participate. These are offered as a suggestion and should be adapted to fit your audience. This type of assessment is typically conducted among existing members.

- How are you involved with [newsroom] as a member? Please select all that apply. (MPP recommends listing all the ways you invite audience members to participate.)

- I read

- I comment

- I share stories

- I attend events

- I’ve been a source

- I’ve contributed sources

- I’ve contributed proofreading

- I’ve contributed other research help (please describe in the next question)

- I’ve contributed tips or story ideas

- I offer financial support

- I volunteer (please describe in next question)

- Other

- Please elaborate on how you’ve contributed and any other ways you are involved with [your newsroom].

- For the ways you’ve participated or most often participate, what prompts you to participate?

- In 200 words or less, why are you a member of [newsroom]?

- Are there any other news organizations that you participate in? (By participation, we mean ways you are involved beyond making financial contributions.)

- Is there anything you would change about the experience of being a member?

Read about how MPP conducted a similar assessment with De Correspondent’s members.

For an excellent example of a motivations assessment, see how Mozilla conducted audience research to better understand what motivates their participants to contribute code and other value-adds to their community of open source technologists.

Specifically, they conducted interviews with their participants about how each person discovered the open source community, what worked and what didn’t during the onboarding and engagement process, and the good and bad parts of the community.

Based on their process and sessions, they were able to identify a set of key reasons people contribute to the Mozilla community, including a self-motivated desire to learn and to feel a part of a like minded community.

How do we find out if members are satisfied?

Use a satisfaction assessment to find out whether your members are happy with your membership program.

Neither a membership program nor memberful routines are “set-it-and-forget-it” efforts. You should continually iterate on both, especially as the number of members and participants grows. A satisfaction assessment gauges your members’ level of satisfaction with a particular part of your program, product, or service. The research and data you gather will then help you iterate on your existing product to make it more desirable.

For this kind of assessment, MPP recommends you use a survey or a Net Promoter Score (NPS) as a starting point, and then if you need deeper feedback, ask your survey respondents to opt-in to an interview with a member of your team.

A Net Promoter Score is used to gauge the enthusiasm of your current users. Essentially, it is the question: “How likely is it that you would recommend our company/product/service to a friend or colleague?” The scoring for this answer is based on a 0 to 10 scale. Most senders also give people an option to elaborate on your score, which can give you helpful qualitative feedback.

NPS surveys are most useful as a way to track changes in users’ feelings about your product, which means they’re most effective if you send them at consistent intervals, or automate them to go to a certain number of people a month. A downward trend in your NPS can tip you off to waning interest that can later cause retention challenges. To use NPS to assess member satisfaction, you would replace “company/product/service” with “membership program” in the standard NPS prompt.

NPS scoring is a bit counterintuitive because it assesses how likely a respondent is to promote you to others as a sign of their satisfaction, rather than explicitly asking them how satisfied they are. A person who gives a score of 6 or below is considered to be a “detractor.” They are perceived to be unsatisfied because they aren’t very likely to recommend you to others. They might even give a negative review.

A person who gives a score of 7 or 8 is considered to be “passive” and satisfied, but not particularly enthusiastic. You’re less likely to lose them, but you’re also unlikely to gain new users through their word of mouth. A person who gives a score of 9 or 10 is a “promoter.” These people are loyal enthusiasts who will likely fuel your growth by recommending you to others. If you have an NPS of 9 or 10 for your membership program, you are well-positioned for a referral or ambassador campaign, which MPP offers advice on later in the guide.

MPP recommends contacting those who give you a score below 7 to see if they would be willing to participate in a follow-up interview so that you can learn more about what would improve their member experience.

Several online survey tools, like SurveyMonkey, offer a Net Promoter Score template or the capability to build your own NPS. If you have an email list for your members, some email service providers (ESPs) are capable of automating the delivery of an NPS survey so that a certain number of randomly selected members receives the question on a frequency that you set. Or, your ESP likely can do this with an integration, like Survicate’s integration for MailChimp. An NPS survey is particularly useful for smaller teams who need to automate feedback, or for organizations whose membership program has grown too large for a conventional survey to be time efficient.

For a more in-depth look at how some businesses sync NPS results with their tech stack to make data-driven decisions, see this Medium post by Klarna product manager Thomas Gariel.

MPP also recommends periodically assessing members’ satisfaction with elements of your program through a more detailed survey. Membership platform Steady encourages its clients to ask their members which benefit they value the most, and which benefit they value the least. You’ll likely notice some patterns among which benefits perform best, which can also help point you to insights about what motivates your members. Find more information on how to iterate on your membership program in “Designing a membership program.“

Membership Puzzle Project has seen few examples of in-depth satisfaction assessment surveys for membership. The research team will offer an example of how a newsroom used a satisfaction assessment survey to iterate on an email newsletter as an example. The same practices can be applied to a membership program or a participation opportunity.

When EducationNC in North Carolina in the U.S. wanted to find out what the most loyal readers of their Daily Digest thought about the newsletter, they sent the following survey to the 5-star readers on their MailChimp list (MailChimp uses a star rating to denote how frequently a subscriber opens emails. Readers with a 5 star rating open the most frequently). Their goal was to collect specific feedback on this newsletter in order to ensure the retention and satisfaction of their most engaged readers. The survey asked:

- When did you begin to receive the Daily Digest? Please select the option that best describes when you subscribed for this newsletter. [multiple choice]

- How often do you read the Daily Digest? [multiple choice]

- What is your favorite part of the Daily Digest? [multiple choice]

- Currently we send out the Daily Digest at 9am. What time would you like us to send it out? [multiple choice]

- Do you receive updates from us on any other platforms? [multiple choice]

- Why do you care about the subject of education? [open ended]

- What else could the Daily Digest provide? [open ended]

- Mebane Rash, the CEO and editor-in-chief of EducationNC, writes and curates the Daily Digest daily. Does it matter to you that Mebane is the voice behind the Daily Digest? [multiple choice]

- Can someone from our team contact you to schedule a short, ~20 minute phone call to learn more about email readers like you? [multiple choice]

See MPP’s case study on VTDigger’s audience research approach for another example of this kind of assessment in practice.

How VTDigger gets and uses a steady flow of audience feedback

Their suite of surveys and commitment to always following up with respondents gives the staff a highly useful picture of their audience.

Another example: in 2019, Zetland in Denmark went on a “roadshow” to meet its most ardent members in five cities outside Copenhagen. Their goal was to hear what they found most valuable about being a member.

In those conversations, Zetland learned that members wanted to be able to share Zetland’s journalism.The trip planted the idea for a new member benefit: the ability to create a package of favorite Zetland stories that members could share. After the roadshow, Zetland sent a survey to all of their members (not just the superfans) to check that this feature was something other members wanted. They received 1,600 survey responses that validated what they heard in-person.

How Zetland retained its members through coronavirus and a recession

Offering discounts for membership is a delicate balance. If you discount it too much, you risk devaluing membership.

If you’re not sure what type of data you need to gather about your audiences at this stage, you can use the Audience Research Compass. This exercise will ask you a few key questions about where you’re at in your membership journey in order to point you in the right direction.

How do we generate insights from our audience research?

After you finish collecting your data, the next step is synthesis – the process of making connections and finding patterns in your data. Synthesis tells you what you should pay attention to.

Many organizations are tempted to skip the synthesis process. This is a mistake, because when you sit down to develop audience segments or make decisions based on the data, you’ll be swimming in “noisy” data that makes it hard to identify what is important for you.

For surveys, particularly those with pre-filled answers, the synthesis process will be fairly straightforward. For example, if the vast majority of your survey respondents said they didn’t want any more swag, then you don’t need to analyze that further. You should feel confident that you should stop focusing on swag.

However, interviews and focus groups will likely yield messier data that requires synthesis before you can infer next steps from it.

There are many ways to approach synthesis. For a simple, accessible synthesis process, MPP will highlight an approach from former research director Emily Goligoski. If you want to go a step further, MPP recommends the process outlined by UXMatters.

First, you need to identify the major category of data you want to extract for further analysis. Below are the four categories of data that are used the most often to make product decisions and where you might find them. You can likely find these categories of data in any type of data collection (from surveys, to interviews, to focus groups) so it’s important to narrow down what you’ll look out for during this synthesis process.

- Behaviors (what users do): Individuals’ patterns and propensities to pay. You can use web and email analytics, event attendance, purchase history, and survey and interview data to understand this.

- Attitudes (what users think): The decisions, including lifestyle, career, brand affinity and activity choices that users make and that indicate what they care about. To learn about attitudes you can look at behavioral, survey, and interview data alongside demographic information.

- Demographics (who users are): The most basic kind of audience background information, including age, life stage, relationship and family status, gender, ethnicity and income.

- Geographies (where users are): Where people live, work and travel. This is gathered through web analytics and geolocation data, app downloads and app usage information from mobile devices.

For example, when assessing the viability of a membership program and what would make it valuable to your most loyal audience members, you would likely focus on a combination of behavioral and attitudinal data points, such as the frequency with which individuals are returning to use your product(s), the number of individuals you can identify who have a “high” frequency, and what those people have to say about the value of journalism and whether they’re willing to pay for it.

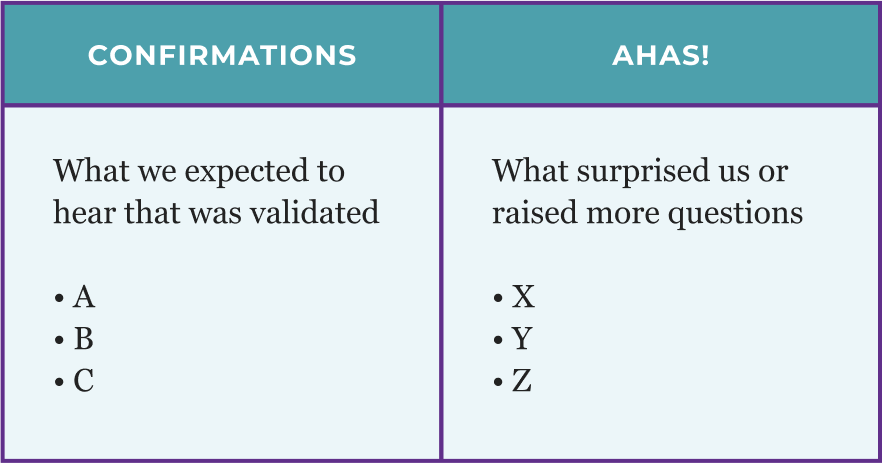

Once you’ve identified a couple types of data to zero in on, you can move on to synthesis. Goligoski recommends identifying one person to be the facilitator. This person will get a large piece of paper or a whiteboard, and split it with a line down the middle.

The left of the paper or board will be for “Confirmations,” or observations that validated your hypotheses, and the right will be for “Ahas!,” or observations that surprised you. Your team will go through your data, giving each idea or insight its own Post-It note or bullet point. Add a +1 each time you hear an idea or insight repeated.

At the end of this process, you will have two useful lists of your audience’s thoughts that you can use for future synthesis and reporting. The insights that appear again and again are worth paying particular attention to, since they represent a strong insight about your audience members. Meanwhile, some of the items in your “A-Ha!” column might warrant further exploration in your next round of audience research to fully understand.

The process we explain above is a comprehensive version of synthesis. Sometimes, if you have just one question and need to know just one thing, a simple clustering exercise can suffice.

For example, Krautreporter’s former editor-in-chief Theresa Bäuerlein wanted to know an answer to one specific question from members: “Why do you eat meat?” She clustered common answers, then reported out the top five answers in her story on the ethics of meat consumption.

How Krautreporter uses surveys to engage, co-design, and grow

Krautreporter is running three to five surveys at any point in time.

For a more in-depth synthesis process, including guidance on how to organize your data and multiple ways of sorting it, see “Analysis, plus synthesis: Turning data into insights from UXMatters.”

How do we segment our audiences and take action?

Segmentation is the process of reviewing your audience research data and grouping it based on distinct behaviors, attitudes and/or demographics. Segmentation lays the groundwork for actionable insights, and can only take place after you’ve synthesized your data.

Here’s why segmentation is so important: your audience is not a monolith. It is composed of different sub-communities or segments, and until you discover those segments, you don’t really know who your audience “is” and you can’t take any action. When you can accurately segment your audience, it means you know something vital about them.

Segmentation begins with grouping audience members based on shared characteristics. Remember that in the synthesis process, you likely organized interview data on particular categories, such as behavior or demographics.

Now, you’ll begin to cluster that information until you start to see distinct groups emerge. For example, if you are a newsroom that reports on education and notice a portion of your interviewees follow a similar lifestyle and have similar news-consumption needs (e.g., teachers who get to their classrooms early and like to quickly skim major headlines at their desks before their class arrives), this could comprise one segment.

Making the decision to group a segment based on this lifestyle and news consumption need means you’d then look for other groupings with similar lifestyle and news consumption needs to comprise segments two and onward (or in other words, you wouldn’t then create a segment organized around demographics with no lifestyle or news-consumption needs similarities).

As you’ll notice, this process is an art more than a science, and there isn’t a determined process to follow what works for all cases. Similarly to how an editor practices a more subjective story sense (knowing what counts as a story, knowing what makes it to the front page), handle this process with your research sense of what matters and what will be useful and actionable for you and your team.

The research team finds one example of segmentation in the American Press Institute’s research, which identifies the 3 types of news subscribers and how to convert them. American Press Institute explains that each of these three main news subscriber personas or ‘archetypes’ has distinctly different mindsets about paying for news and information: the Civically Committed, Thrifty Transactors, and Elusive Engagers.

Below is an example out of a newsroom – from BBC Media Action – in which they developed segments based on political engagement attitudes and behaviors. They used these segments to determine how to best reach each group.

No matter how big your team is, it’s unlikely that your news organization has the bandwidth to equally serve each of these segments – and it’s probably not a good use of your time. A simple way to prioritize once you have development segments is to map them on a simple two-by-two matrix. “Effort” indicates how much work it will take to reach that segment, and “value” indicates how much your organization will gain by reaching that segment.

For example, if there is a segment of people who don’t already regularly use your product or who weren’t showing signs of wanting to engage with your work, place them in the bottom right corner of the matrix – and don’t think about them again.

| Low Effort | High Effort | |

| High Impact |

Highest priority |

Higher priority |

| Low Impact |

Lower priority |

Lowest priority |

Designed by Jessica Phan. Content courtesy of this Poynter piece by Emily Goligoski, 2019.

MPP recommends focusing on the “low effort, high value” quadrant. Those in the “high effort, high impact” quadrants will be time and cost intensive to convert, but because they will add significant value to your organization, you should focus on understanding their behaviors and attitudes next.

When applying this to your membership program, you could also use this matrix to identify which benefits are worth including. In that case, benefits that would be challenging to implement should only be offered if they can make the membership program much more valuable for your potential members.

Sometimes you might already know who your target users are, but don’t know how to serve them, or what needs might cut across multiple segments.

This was the case for Frontier Myanmar. So, after the newsroom segmented its audience members by profession, they used audience research to identify each profession’s information needs, which they used to design the newsletters that became the core benefits of their membership program.

How Frontier brought a membership model to Myanmar

They began by identifying five professions who needed the journalism Frontier Myanmar produces.

At this point, some people might be wondering: do we then need to make a series of user personas? User personas are fictional characters created to represent a user type that might use a site, brand, or product in a similar way. In other words, newsrooms folks use user personas to represent specific segments of their readers.

Here’s MPP’s stance: not everybody needs to develop composite humans to represent each audience segment. Do this only if it would be helpful and useful for internal planning (e.g. if you think your team will find it easier to understand how to design for Michelle than “our superfans”). See the Mozilla example the research team mentioned previously for a great example of a series of user personas that came from an audience research process (including the independents, the leaders, the fixers, and the citizens).

Black Ballad does not use personas because their goal is to serve one particular segment exceptionally well – Black British professional women between the ages of 25 and 45.

How Black Ballad turns member surveys into new revenue streams

Their goal is to be the one who knows the Black British professional woman better than anyone else – and to monetize that knowledge.

How can we conduct audience research as a single-person newsroom?

If you’re a one-person newsroom or the only person working on audience research at your organization, MPP understands that you can’t do everything outlined in this section.

Above all, conducting effective audience research on a small or one-person team requires extreme clarity on what information you need to gather in order to make a product decision. As mentioned earlier, you should always undertake audience research in connection with an organizational goal, whether that’s improving an editorial product or finding out why members support you.You can use MPP’s research design brief to help focus your inquiry.

With limited bandwidth, you want to limit the amount of extra information you need to sift through to find the information you really need. An MPP rule of thumb is that when conducting interviews, you’ll start to see patterns emerge in the responses beginning with the seventh interview. When you can see an answer to your problem emerge from the data, you have enough responses. Design researcher Erika Hall, author of “Just Enough Research,” calls that the “satisfying click.” If you can’t yet see a pattern, you need more responses.

The research team offers the following additional advice on managing audience research on a lean team.

Choose surveys over interviews, and interview intentionally. Interviews are hard to conduct even on a larger team. On a tiny team, start with a survey. You can make it easy to conduct follow-up interviews or a focus group by adding a question to the survey asking if they’re willing to be contacted in the future with follow-up questions. If you need the level of detail that interviews provide, consider setting a goal of one or two 30-minute interviews a week. Establishing a routine will help make it manageable, and doing that after a survey will help you make the interviews more targeted.

Automate it. Explore ways to automate audience research. De Correspondent’s onboarding series for members includes a survey 30 days after joining to hear about their experience, and again at three months, six months, and as members approach their one-year anniversary. VTDigger added a field to their newsletter unsubscribe page requesting that readers “Please let us know why you unsubscribed.” Because the newsletter is the primary means of engagement with loyal readers, they see feedback on this product as a vital temperature check on their membership strategy writ large.

From this form, VTDigger learned they have a lot of seasonal residents and second-home owners, so they often get unsubscribe messages like this one: “I am away from VT for a while and have so many emails!” Eventually, they would like to be able to offer a “restart” date for their newsletter to allow these folks to freeze their subscription for a certain period of time. But they haven’t reached a point where the potential impact of this change is worth the effort and cost to implement it. They’re okay with losing newsletter subscribers over this type of complaint for now.

You do not have to act on every bit of feedback you get. VTDigger’s decision to not explore a solution for seasonal residents at this time is a good example of having clear priorities about what to act on. Another comes from Sherrell Dorsey, the founder, publisher and sole full-time employee of The Plug, which covers the Black innovation economy. Dorsey is emphatic that you don’t have to do everything that members or subscribers ask you to do.

When surveying early newsletter readers, Dorsey saw two distinct camps emerge among her subscribers: “techies,” who wanted highly technical reviews on products, and a more general audience that was interested in the innovation economy. Dorsey knew that she didn’t want The Plug to be about intense product reviews, so going forward she focused on delivering on the preferences expressed by her non-techie audiences. Some readers have also urged her to improve the user experience of The Plug, but because they’re still meeting their growth goals, she’s decided that addressing that need isn’t urgent.

Consider using an impact/effort matrix to help map out what insights to act on immediately, what can be handled later, and what can be set aside for good.

Recruit help. MPP knows that the synthesis process can be daunting, both in the skills and the time it requires. But conducting audience research without a robust synthesis process will leave you lacking actionable insights. Consider asking for help here. Radio Ambulante worked with a professor who offered to help the newsroom with analysis if Radio Ambulante authorized her to use the anonymized data set in a data science class she teaches. OpenIDEO, an offshoot of the pioneering design thinking company IDEO, has chapters all over the world which frequently take on local innovation projects.

Check out your local university to see if they offer training or support in some way (you’ll find design thinking courses in the business school, most likely, but you could also check out sociology departments). And Stanford University’s d.school offers plenty of free online resources, including a library of design questions and a design starter kit. Don’t neglect to ask your member base, as well.

How can our newsroom use audience research beyond membership?

In this chapter the research team focused on ways audience research can be used to assess the motivations, habits, and values of members, potential members, and participating audience members. But learning about audience research processes for other product development goals can be generative.

Below are few common ways audience research is used beyond membership.

Product design and development

Audience research can be used to guide the design of newsroom products. In this context, audience research is typically referred to as “user research.” See below for examples and resources for this type of research:

- See IDEO’s Design Kit for an overview of research methods, along with case studies on how different organizations used human-centered design to get real results.

- See the Tow Center for Digital Journalism’s Guide to Journalism and Design for an academic overview on systems thinking, human centered design, and research methods best practices.

- See the Lenfest Local Lab’s Guide for a deep dive on research in service of a newsletter’s components, order and design, including how it uses research design and processes (Part 1), evaluates data and creates user personas (Part 2), and implements changes (Part 3).

- See this Medium post by Nicolás Ríos and former MPP research assistant Aldana Vales for a deep dive on how they partnered with Documented (a nonprofit newsroom that covers immigration in the New York area) to survey undocumented Spanish-speaking New Yorkers.

- See how the New York Times conducted research, designed and iterated the New York Times’ Parenting site.

Information needs

Knowledge about information needs is a bedrock piece of audience research for all newsrooms. Information needs assessments uncover the types of information or coverage that community members are looking for. Finding this out usually entails going beyond your existing audience. The needs you surface in this kind of assessment can help you structure your newsroom, identify coverage areas, and design new products. See below for examples and resources for this type of research:

- See the Center for Cooperative Media’s how to conduct an information needs assessment.

- See KPCC’s process for designing census coverage for early childhood coverage for an example of an information needs assessment.

- See Foothill Forum’s survey of Rappahannock County, Virginia, as well as a Rappahannock News story about the results

Are there times when we shouldn’t do audience research?

The short answer to this question is: “yes.”

There are a few instances when you may be better served by not taking your questions to audiences first. Former MPP research director Emily Goligoski identifies the following as times when the value of audience research is limited:

When you’re having trouble making cross-department decisions. Odds are, the cross-department bickering might be better off solved with an internal meeting or offline conversations, possibly with leadership involved. Tie-breaking isn’t the most thoughtful use of the time, care, and money that audience research entails.

When your organization wants to be perceived as one that listens, but actually isn’t going to use the findings. Don’t bother conducting audience research if you don’t have the intent to use and implement what you learn.

When you want to solicit positive feedback to make yourselves feel good. The research team knows this one can be tempting! But audience research is about real reactions and critical feedback, not collecting book blurbs.

When you want to choose between different calls to action. It’s useful to know when A/B testing is a better fit for answering your team’s questions. For example, many specific email newsletter related questions (e.g. What tone should my subject line have? Who should the “sender” be?) can best be answered by A/B testing your experimental copy against your standard copy and seeing which one performs better in terms of open and click rates.

When it isn’t connected with an organizational goal. If an audience research effort isn’t connected to an organizational goal, then you are likely wasting your team’s time and your audience members’ time. Without a goal, you’ll struggle to identify what type of insights you need to gather and what questions to ask, making it likely you’ll have to reach out to audience members again in the near future. If this happens, you risk developing survey fatigue among your audience members – ask them too often, especially if they don’t see their responses being acted on, and response rates will likely decline over time. An organizational goal could be assessing whether membership is viable for your organization, for example.