Newsroom overview

The Compass Experiment is a local news laboratory founded by McClatchy and Google. They publish Mahoning Matters and the Longmont Leader

Youngstown, Ohio

2019

190,000

The Compass Experiment, a local news laboratory founded by McClatchy and the Google News Initiative, launched Mahoning Matters in 2019 in Youngstown, Ohio. They launched on the heels of Youngstown’s longtime local newspaper, The Vindicator, shutting down.

Although the Compass Experiment newsrooms receive funding to get off the ground, they have a goal of becoming financially sustainable in the next few years, so as the team conducted its initial audience research, audience revenue was top of mind.

This case shows how the Compass Experiment conducted focus groups without an audience of its own in order to assess membership viability. It also shows how they changed strategies when the coronavirus pandemic derailed their plans, what they’re hearing from their earliest supporters as they approach their first anniversary, and how they’ve applied those learnings to the launch of their second Compass newsroom in Colorado.

Why this is important

Audience research can prevent you from making costly mistakes, especially in the pre-launch phase, when you don’t yet know your audience members. Without an audience research sprint, The Mahoning Matters and Compass Experiment teams wouldn’t have had a strong sense of who their audience was, what they wanted, and whether their audience had any interest in financially supporting their mission.

But it can be hard to recruit audience research participants when you don’t have an audience. The Compass Experiment’s partnered with other local organizations to get the word out – a smart strategy that a newsroom of any size, especially if you’re assessing information needs or designing a product intended to help you reach new audiences.

Early audience research results indicated that Youngstown residents wouldn’t support a publication with a paywall, which pushed the Compass team toward membership as their model. Early audience research also pointed the team toward emphasizing their financial situation to their early readers as a way to prime them for future reader revenue and membership requests. It also gave them a mission: to be both the journalism of protection – uncovering corruption and misdeeds – and of discovery – telling the full story of Youngstown, successes and all.

What they did

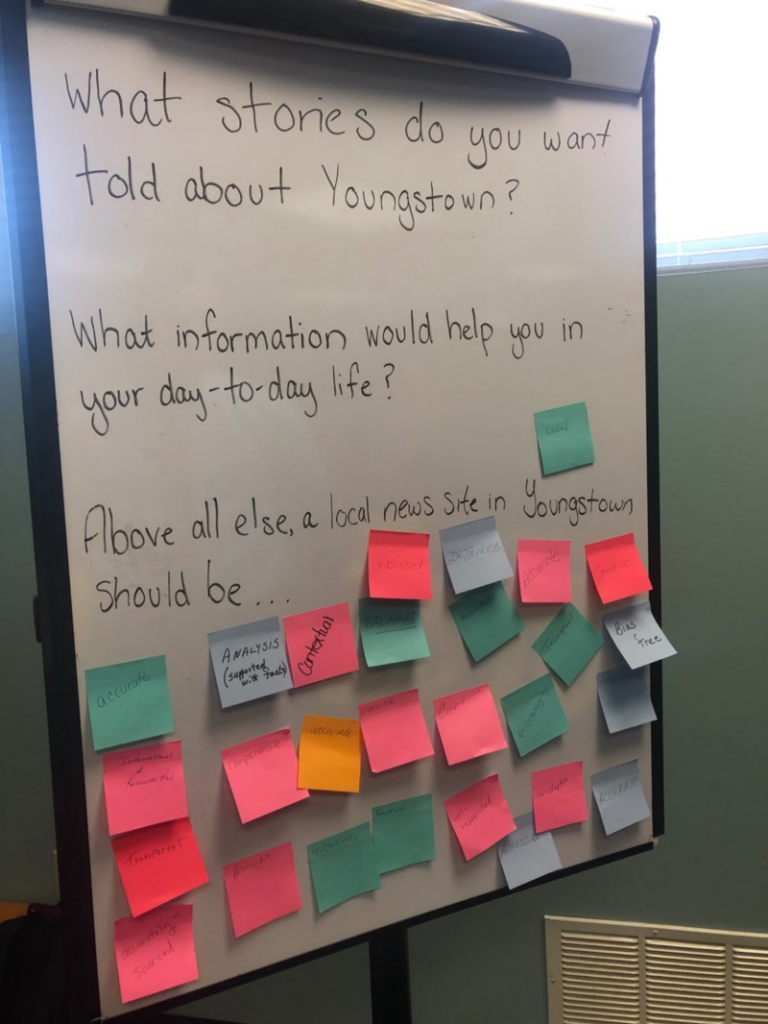

The summer before Mahoning Matters’ October 2019 launch, the Compass Experiment team headed to Youngtown to find out what residents really wanted from a local news organization if they had the opportunity to start from scratch – and whether they would be willing to support it financially. The city’s only newspaper, The Vindicator, closed in August 2019, and the Compass Experiment team wanted to know how much residents understood how that was linked to the need for audience revenue. They settled on focus groups since they wanted to collect authentic thoughts, feelings and conversations from this new community they were getting to know.

Throughout August, they hosted a series of focus groups at local library branches across Youngstown. The library helped recruit participants by hanging flyers inside their branches and sharing the information on their social media channels.

Across three sessions, the Compass Experiment was able to talk to 60 Youngstown residents. Abby Reimer, Senior Manager of UX & Strategic Projects at McClatchy, led the focus groups, which she documented in this Medium post.

Reimer focused the focus groups on guiding questions like: What stories need telling in Mahoning County? What information would improve your day-to-day-life? Reimer’s synthesis for the Compass team focused on what residents strongly wanted, what they strongly didn’t want, and what they were most passionate about.

That winter, Compass Experiment General Manager Mandy Jenkins started recruiting to hire someone who’d be in charge of growth and launching a new membership program for the newsroom. They had big plans: exclusive content, live-events at breweries and summer fairs, and swag.

Then, COVID hit.

The Compass team decided to revise their plans to launch membership. They realized it was nearly impossible to come up with alternatives to their previous launch plans. Of course, events were out – and exclusive content felt cruel and out-of-mission for Mahoning Matters to start offering right as coronavirus and Black Lives Matter protests were reaching their 2020 peaks.

Instead, Compass decided to again double down on audience research. This time, with in-person focus groups impossible and an existing newsletter list of readers, they opted for a survey. They sent the survey to 50 people who financially contributed to the newsroom in the past year. They wanted to know: what do you, our early supporters, like the most about what we’re offering so far? What can we improve? See here for that Mahoning Matters Contributor Survey.

The results

The focus group process in August 2019 helped the team determine what, exactly, their new newsroom would cover. Attendees wanted to easily access and understand public resources like job listings, veterans’ resources, and affordable housing access. Overall, they heard from attendees that Mahoning Matters would need to both be the journalism of protection – uncovering corruption and misdeeds and of discovery – telling the full story of Youngstown, successes and all.

They also heard loud and clear from the focus group participants, essentially, “If your newsroom has a paywall, we are out.” Reimer’s notes showed the majority of participants felt strongly that they local news should be accessible for as many people as possible. This has pointed Compass Experiment team to membership as the best path forward.

The team received 20 responses to the survey it sent to the site’s first 50 financial supporters. This was less than the team expected for a completion rate, and they planned to run a virtual focus group with survey respondents who opted into one, but only four people indicated interest.

The team was still able to gather some interesting insights, including what drove people to support them: the newsletter, watchdog journalism, and hyperlocal news. Many said they had been Vindicator subscribers. One said, “The Vindicator closing was a shock to me, and I don’t want that to happen, again.” Another said, “We need independent local journalism dedicated to Youngstown.”

This October, the Mahoning Matters team plans on harnessing the excitement around their one-year anniversary to conduct a wider survey and convene another focus group. This time, they intend to send out the survey to their entire email list to take a temperature check on how satisfied their readers are with their work, one year in.

What they learned

It’s hard to conduct audience research without readers. The Compass Experiment team found it difficult to recruit folks to attend their focus groups early on without an existing base of people or readers. The early focus group participants were mostly a mix of people recruited from Jenkins’ blog post in July announcing that the Compass Experiment was coming to Youngstown (Jenkins had included a dummy email list for people to sign up for updates) and folks that the local libraries recruited from hanging flyers. Another thing the team learned: if you want to attract people to your focus groups, serve lunch!

Especially in the early days of a newsroom, consider creative ways of reaching the community members you seek to serve. Some creative ways include partnering with a local library to help recruit participants, or purchasing the email list of potential partners in community media. to give you a starting point. The Compass Experiment team was able to put their own learning here into practice when they launched their second site, The Longmont Leader, in Longmont, Colorado.

This time around, the team knew they needed help finding an early target audience. Given the statewide lockdown in Colorado, they had to do surveys and small group discussions virtually rather than at fairs, farmer’s markets, or local microbreweries. So, instead of relying on Facebook lead acquisition and Google ads to build the initial audience list, they purchased the digital assets of the Longmont Observer, a nonprofit community news site, including its email list of nearly 1,000 local readers.

They sent a survey to this list of 1,000 people and, in only a few days, received 128 responses in return. This time, enough people opted in for the focus group that they were able to host three virtual focus groups and dig into their early audiences’ thoughts on local news in the area, their information needs, and what they liked (and didn’t like) about living in Longmont.

Key takeaways and cautionary notes

Be clear with your audiences about your financial situation. Around the same time the Compass Experiment launched a local news site in Youngstown, Ohio, the local newspaper in Youngstown (The Vindicator) was shutting its doors.

The Compass Experiment learned from early focus groups that people in Youngstown, even die-hard news consumers, had no idea the Vindicator was in such a state of distress. The Compass Experiment is making sure that both of their newsrooms are clear to tell people, “here is our financial situation – we have this runway with Google, but it will run out. New advertising money is not coming in. We will need your help.” They plan on continuing to emphasize this messaging with their readers and early contributors as they gear up for an eventual membership launch.

Other resources

- Compass Experiment, Medium: “Listen, learn, and launch: How we brought the community into the development of the Longmont Leader.”

- Compass Experiment, Medium: “We’re creating sustainable local news, and we need your help”

- Compass Experiment, resource: Mahoning Matters Contributor Survey

- Compass Experiment, Medium: “Charting a new (collaborative) course in Mahoning County”